I conceptualize learning as a self-changing process during

which my thinking is greatly influenced by experience with new information, or

the various sources of knowledge that I experience through my engagement with

other people, objects, situations, events, and most important of all, ideas. It

took me a long time to come to where and who I am. Along the way I had absorbed

a smorgasbord of specialized knowledge: linguistics, English literature,

language teaching and arts organization management. However, I experienced more

changes in the past two years of my Ph.D. grogram in LCLE than I had previously

experienced. James Paul Gee suggests people to beg, borrow, or steal new ideas

to become smart in this fast-changing and complex world. “It requires that all

of us, young or old, remain open to discovery and grow to be distrustful of

long-held and cherished beliefs that we have not closely inspected for a long

time (Gee, 2013).” This has been so true to me for the past two years during which

these “begged, borrowed and stolen new ideas” regenerated me by challenging my

old structure of knowledge and escalating me step by step from the little

confinement of my previous unreflective life to a much broader intellectual

landscape. Not exaggeratingly, I find myself a different person everyday with

my ontological self shaped and reshaped by the incorporation of new knowledge

into my old schemata.

This constant expansion of knowledge gives rise to the

change of lenses with which I look at things around me, and as a result, new

connections between two different things, or between my present and the past are

always built up. For example, I used to see language as a unique and the most

important means of communication. But semiotics enables me to see language as equal

as other signs of human communication, and human communication is multimodal. Significance

for this shift in perspective? Needless to say, linguistic theories—even those

that fuse language and social practice, such as Halliday’s Systemic Functional

Linguistic theory and Austin’s speech act theory—can no longer lend themselves

to the interpretation of such a changing landscape of communication, given the

ease with which images, sounds, and movement can be tapped for signification.

This is because the direction of the discipline in which Saussure (generally

believed to be the founding father of linguistics) leads is mainly concerned

with the signs themselves and the underlying structure which gives meaning to

each other, while unfortunately cutting the relation between the signs and the

realities they represent on the one hand and dismissing the significance of the

acting subject on the other.

This shift in perspective therefore enables me to see a

symmetry between the producer and receiver of the sign that contributes to the

success of a communication. It can also be paraphrased by citing Seboek (1994):

“signs have acquired their effectiveness through evolutionary adaptation to the

vagaries of the sign wielder’s Umwelt (p.12).” Paradoxically, the reductionist

perspective allows me to see permanency among fleeting changes, i.e. the circle

of communication remains the same if the internet and all those smart terminals

used for communication are just considered new extensions of perception human

beings have never ceased to create extensions of themselves) that have

constantly altered our Umwelt (Uexhüll, 1940). The crux of success still

consists in the ability of both the producer’s and the receiver’s mutual

understanding of these extensions. An interesting way to explain why the

internet tends to gather like-minded people together is that people with

similar Umwelts find communication easier and more economic because of their

symmetrical understanding of the signs produced by each other.

Sebeok, T. A. (1994). An introduction to semiotics. London:

Pinter Publishers.

Uexhüll, J. v. (1940). The

theory of meaning. Semiotica, 42 (1), 25-82.

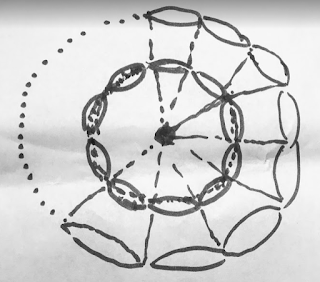

How I learn: I picture myself in the middle as a dot. I gain

knowledge through various sources and the new knowledge is connected with my

old knowledge (sometimes revolutionizes my old paradigm). At the same time, the

knowledge gained serve as lenses through which I look at the world around me or

make predictions about the future (the inner circle). These lenses enable me to

see more and farther, represented as the outer layer of knowledge, which can be

future lenses. This is how I model my intellectual growth. But there is a paradox:

the more I learn, the more uncertain I have become, and the more I realize how

small I am. This can be illustrated by the fact that as the known becomes

larger, represented by the expanding circles, there is more exposure to the unknown.

How I learn: I picture myself in the middle as a dot. I gain

knowledge through various sources and the new knowledge is connected with my

old knowledge (sometimes revolutionizes my old paradigm). At the same time, the

knowledge gained serve as lenses through which I look at the world around me or

make predictions about the future (the inner circle). These lenses enable me to

see more and farther, represented as the outer layer of knowledge, which can be

future lenses. This is how I model my intellectual growth. But there is a paradox:

the more I learn, the more uncertain I have become, and the more I realize how

small I am. This can be illustrated by the fact that as the known becomes

larger, represented by the expanding circles, there is more exposure to the unknown.

Comments

Post a Comment